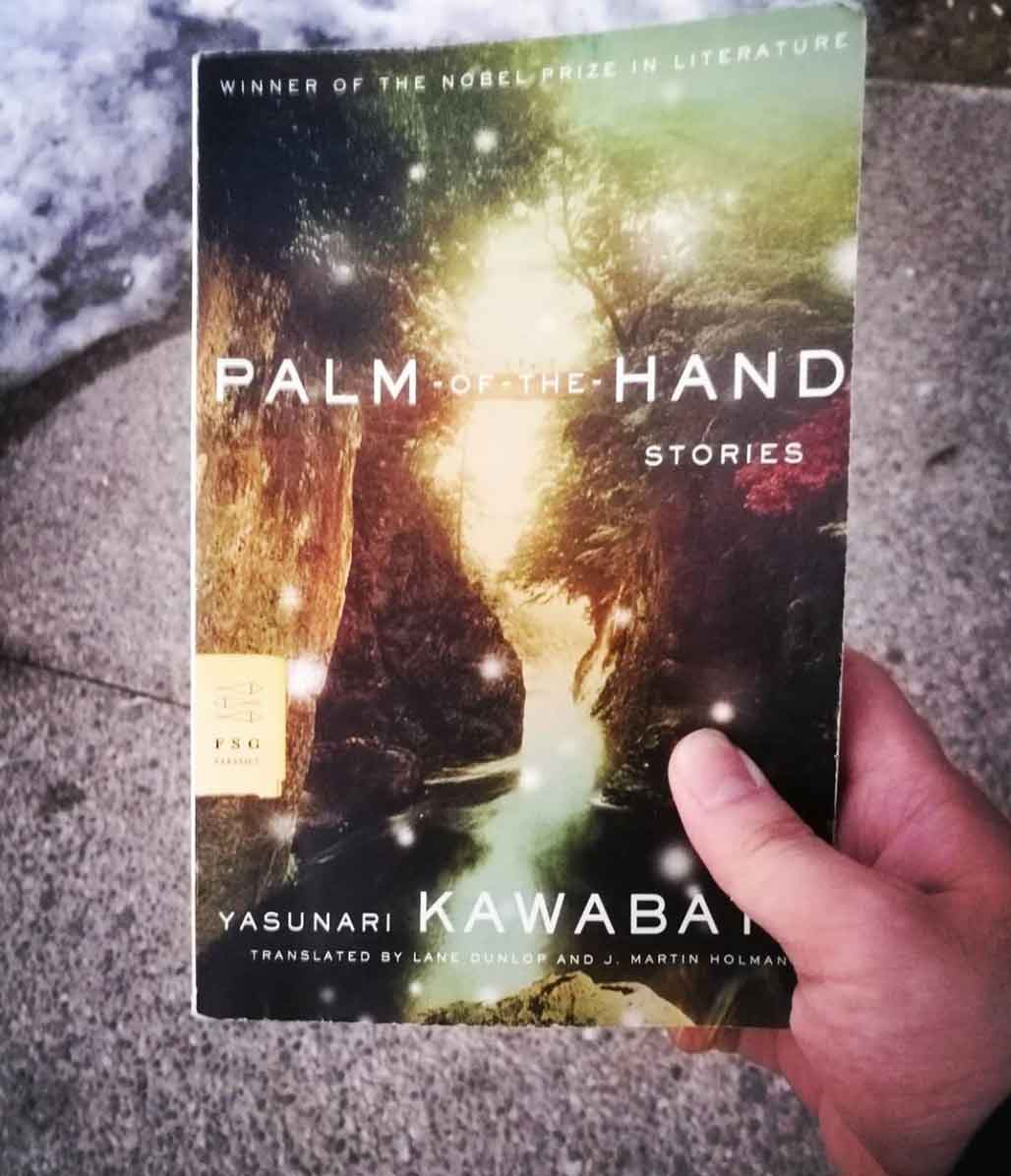

Some of these short, short stories felt shocking and absurd, either because of Kawabatan intention or because of the brutal reduction of the narrative–or both: Kawabata was an avant-garde writer back in the day, influenced by surrealism, cubism, dadaism, and other Western imports; three of the first four stories in this collection of many are dream-tales.

”Marriages of blood relatives had continued through the generations until the girl’s family had gradually died out… She, too, was rather small in the shoulders. Men were probably startled when they embraced her. … The girl, however, enjoyed daydreaming of a strong man’s arms–strong arms that would make her ribs crack when they were wrapped around her. For, although her face looked relaxed, she felt desperate. When she closed her eyes, she saw her body floating on the ocean of life, drifting wherever the tide took it. This gave her an amorous air.

“ The disjointed and pared down writing obscures the connections between the sentences.

From Kawabata’s The Old Capital and Thousand Cranes I sensed a non-Western and anti-individual conception of personhood, one in which human beings can be thought of as repetitions (I struggle for a better word)–some of the short, short stories seem to confirm my suspicions. Scholium The story “Mother,” for example, begins as follows:

“1/The Husband’s Diary

Tonight I took a wife

When I embraced her–the womanly softness

My mother was also a woman

Tears overflowing, I told my new bride

Become a good mother

Become a good mother

For I never knew my mother”

The husband becomes deathly ill, the wife forces the illness into her, they both die from illness, leaving a 3 year old infant behind. The story ends:

“4/The Husband’s Diary

Tonight I took a wife

When I embraced her–the womanly softness

My mother was also a woman

Tears overflowing, I told my new bride

Become a good mother

Become a good mother

For I never knew my mother”

The last story in the collection is “Gleanings from Snow Country.” I felt trepidation about reading the story: this was an occasion that called for solemnity, gravity, midnight–I did not want to read it casually for the same reason I dread treading on a fresh, unmarked field of morning snow (I actually don’t). I’ve read it while un-sober, with the hopes that this would preserve the story for an actual first reading, for when I would be ready.