Landmarks From Before It Was Called Tokyo:

Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo

広重作江戸名所百景展

Co-presented by Stuart Jackson Gallery & The Japan Foundation, Toronto

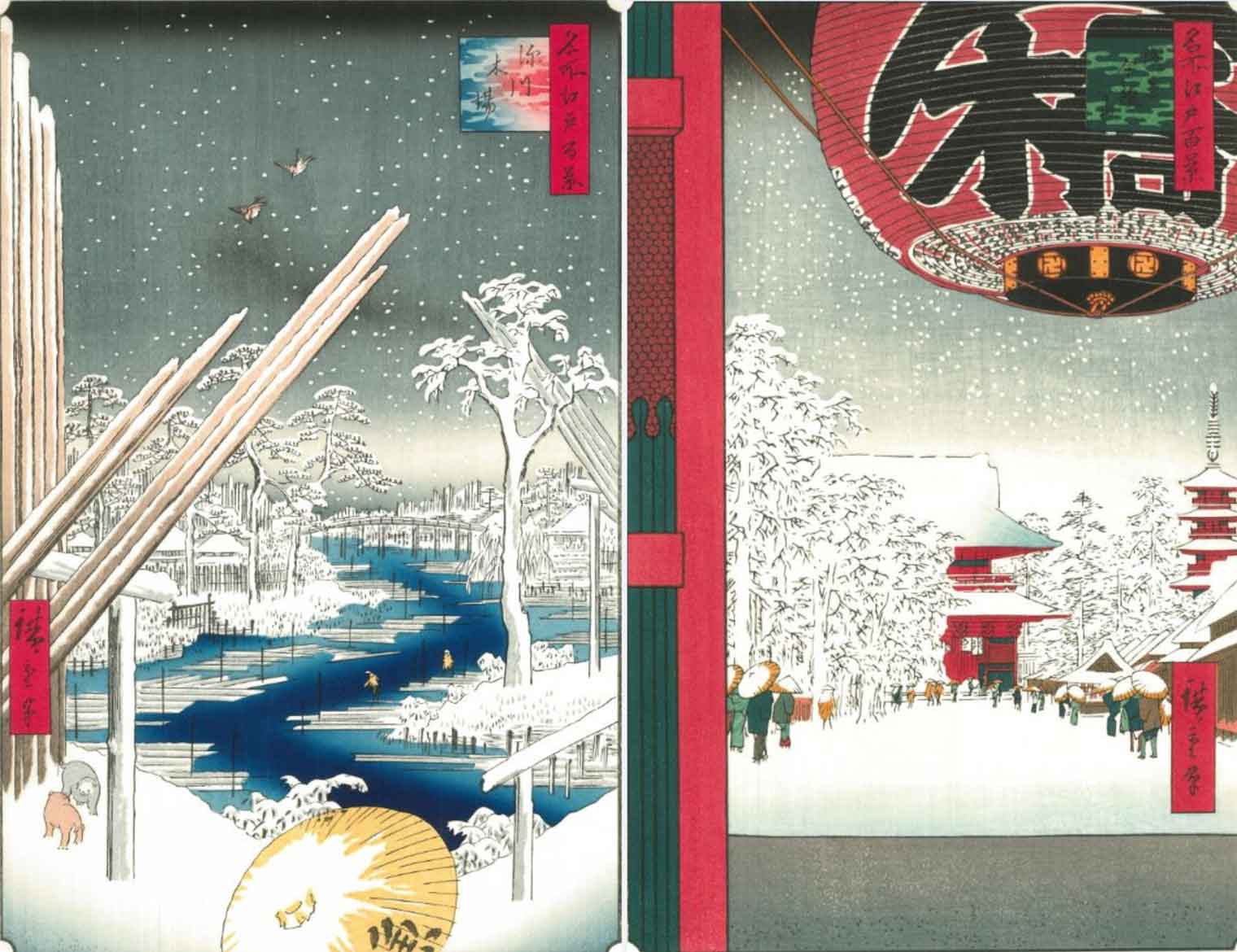

Original print works of One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, for short “Edo Hyaku (hundred)”, by Hiroshige (1797-1858) for your view, together with related works, and contemporary hand-carved, hand-printed reproductions to bring back the excitement and ambience of sophisticated urban life in Edo.

“Edo Hyaku” of Urban Serenity

One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, for short “Edo Hyaku (hundred)” by Hiroshige is a series of multi-coloured woodblock prints depicting the landmarks of Tokyo at the time the city was called Edo.

Hiroshige (1797-1858) was an ukiyo-e artist whose reputation was most strongly established in the genre of topographical prints. This direction towards landmark themes came to Hiroshige, a late bloomer, in 1831 when his artistic breakthrough, Tōto Meisho or Famous Views of the Eastern Capital (Edo) print series was published. In 1833 Hiroshige’s popularity exploded when his series 53 Stations of Tōkaidō Highway appeared.

Across Japan many famous views became the subjects of Hiroshige’s print series, but the city of Edo had a special place in his artistry. In volume alone, Hiroshige created more than one thousand prints of the landscapes of Edo. Among all these books and prints of Edo by Hiroshige, “Edo Hyaku” occupies an even more privileged position.

“Edo Hyaku” is a summit of Hiroshige’s famous view prints. He himself had previously created many series of famous views, as though they were the foothills supporting this magnificent peak. In “Edo Hyaku”, which was created during the last two-and-a half years of Hiroshige’s life, the artist made one last creative leap: Unlike his travelogue prints which had sense of humour and vitality, the urban scenes in “Edo Hyaku” embrace poetic stillness and serenity along with new dramatic elements of composition.

Contemporary researchers say that “Edo Hyaku” had an intention of providing emotional relief from the disasters of that time — the Great Ansei Earthquake in 1855 and the Great Wind Storm in 1856. Hiroshige encouraged the citizens, celebrated the recovery and restoration, and mourned for the victims through his artworks. Having the 2020 Tokyo Olympics in a country deeply hurt by an earthquake in 2011, Hiroshige’s generous, affectionate glance to the city and its residents is more touching than ever.

Original works from “Edo Hyaku”, related works, and contemporary hand-carved, hand-printed reproductions bring back the excitement and ambience of sophisticated urban life in Edo. Nature and the seasons along with man-made structures were fully appreciated by Edo residents who made up a population of more than a million individuals.

Hiroshige’s farewell poem

Azumaji e Fude wo nokoshite Tabi no Sora

Nishi no Mikuni no Nadokoro wo min.

I leave my brush in the East

And set forth on my journey.

I shall see the famous places

in the Western Land.

(The Western Land in this context refers to the strip of land by the Tōkaidō between Kyoto and Edo,

but it does double duty as a reference to the paradise of the Amida Buddha.)