In the corner of the street, near the entrance to Eaton center in Toronto, sits a man with a yellow duck costume. He wears fake glasses and busks with bunch of buckets for people who pass by. Amongst him are preachers of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. I went over and greeted him after he completed his set. I greeted him in Japanese which took him by surprise for no one, he says, who is Japanese can tell that he too is a Japanese.

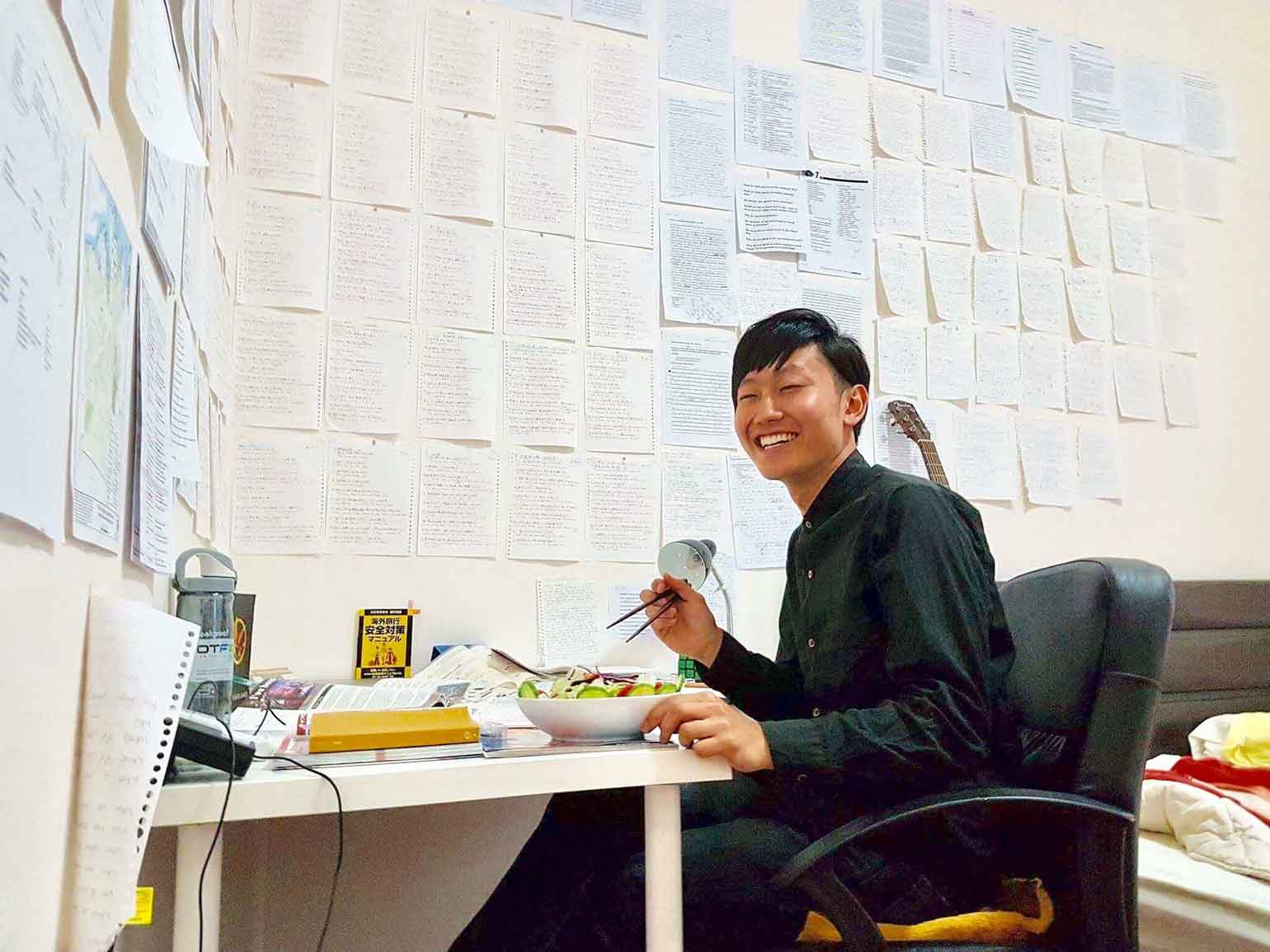

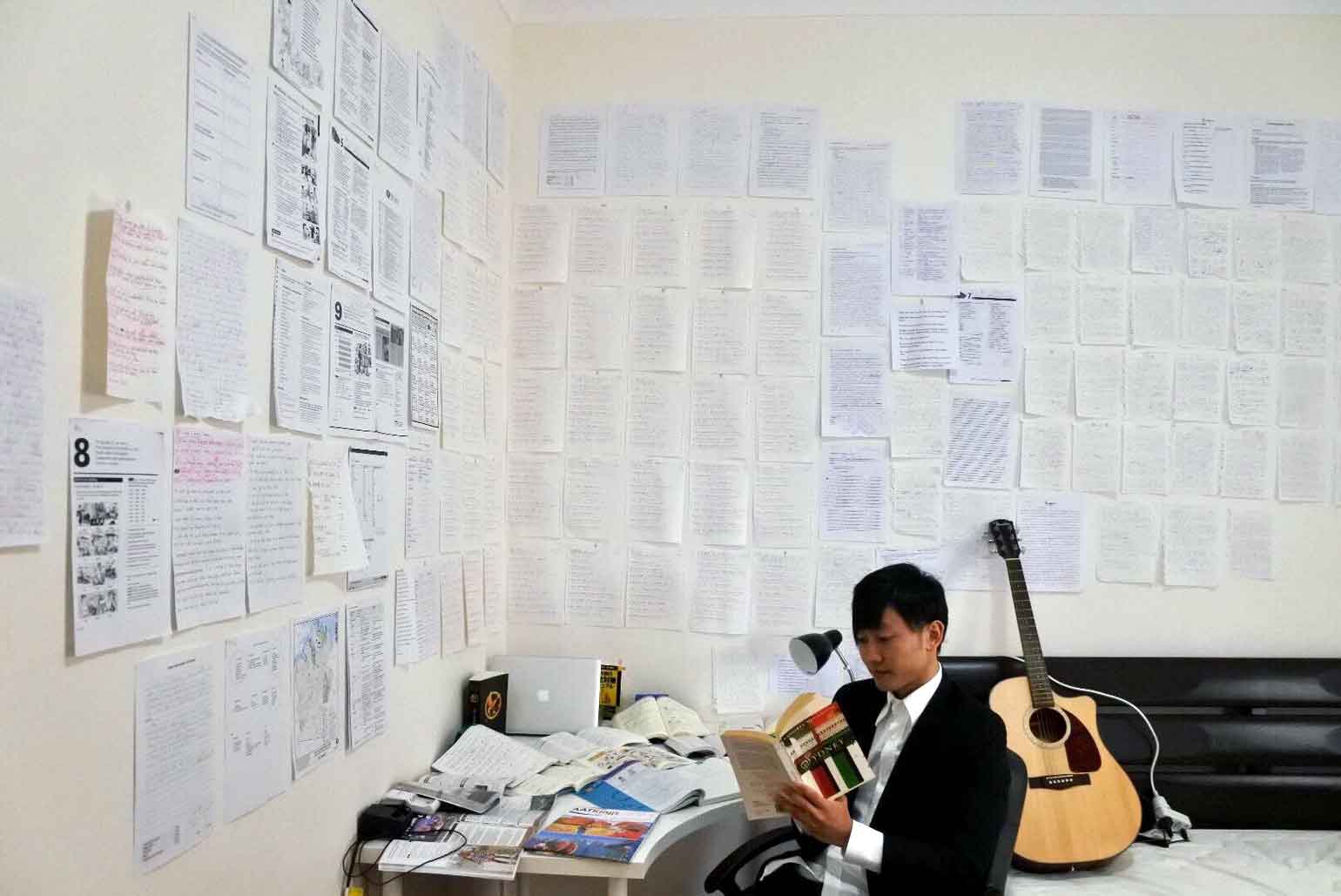

After our first encounter, I did some research and found out that Duckman, aka Takahito TK Nakamura, is more than a street performer with a duck costume and an infectious grin. He is a comedian, actor who made appearances in the popular NHK TV drama, “Battery”, cosplayer and a musician. His mother used to be in “ladies group”, a Japanese motorbike gang group consisting only of women. At less than a 2 week old, he was sent to an orphanage after being strangled by her mother and experiencing serious abuse and neglect. He went back to living with his mother and relatives which lead to more neglect and abuse. After awakening to the “power of comedy”, he performed in acclaimed Yoshimoto Creative Agency for 7 years, specializing in “Jigakuneta (self-tormenting)” comedy. He majored in sociology/psychology at university where he was head-hunted by a professor at Tokyo University, to be an assistant. He is a multi-talented musician, able to sing as well as play the piano, drums, bass guitar and the electric guitar, and was the lead singer and guitarist for his band, “Wallop” which went on to be a finalist for the Sony Next Generation band competition in 2015. After graduation, he studied English in Australia to accomplish his dream, which is to “make people laugh and happy”.

The next time we meet, we are at a café in Chinatown. I had in my mind many questions for this Duckman. This is our conversation.

You have established yourself as a multi-discipline entertainer, Duckman in Toronto. Could you tell us about what you do and what are your future plans?

My plan for the future is to stay in Toronto until summer and then visit Europe, as that was my original plan. I lived in Sydney and New York before, and now I reside here, in Toronto. My original plan was to go to Berlin in spring but my friend in Japan is getting married. So I’m thinking to go back there.

Why was Berlin your first choice?

I pick countries that have diversity and that’s why I lived in Sydney, New York and Toronto. From what I’ve heard, Berlin is a multicultural city with little judgment towards others. My last goal is to visit London in England.

Talking of England and multiculturalism, what are your thoughts on current situation in England, like Brexit?

There are always obstacles like terrorist attacks and Brexit whenever I try to visit England. I was planning on visiting London 3 years ago, 2 years ago and again last year, but I never made it. Everybody told me not to visit there when Brexit happened and I have been postponing my plan since then. That’s why I am still here. I’m unsure of when I’d have the chance to visit England.

What are your main sources of motivation for busking?

The reason why I go busking is to gain recognition through media appearances. One day, I’m hoping to get support from a corporation—maybe an insurance company. I go by the name “Duckman” so I’m thinking of “Aflack” (a Japanese insurance company with a duck mascot), which I think would be funny.

Many Japanese people are afraid of living or visiting abroad as their English ability is generally not great and I was like that 3 years ago. But here I am, working as an entertainer on the streets of Toronto. I want more people to know that living abroad, or studying abroad is not as hard as they might assume. I want to spread courage to people. I’m not anti-Japan or anything, but I think talented youths need to go outside of Japan and their comfort zone. I’m not trying to convince people to come abroad because it’s simply “fun”. There is also more to it than just working at Japanese restaurants and so on.

So, one of your aspirations is to give inspirations to people of the younger generation in Japan to come abroad and explore.

That is one of my many goals. I want more people to know about what I do and I wish to do collaborations with entrepreneurs in the future. One of the obstacles I face while busking is that it doesn’t get me too much money. I can go to countries outside of Japan, but I won’t be able to stay there long-term if I can’t earn money to pay off my rent. I was in New York and I was make a living, but I feel that the countries I can be performing while making living are limited.

In the future, I want to go to developing counties. I have been skeptical of the act of simply sending remittance to those who are struggling. What if the people end up feeling bad about themselves as they are categorized as “poor” by those who they have never met? I wish to somehow give hope to those who are in need. I want to visit people who are in need and do my performances and also tell them about myself and what I have experienced. For that, I need to find sponsors, maybe on platforms like GoFundMe. Then I can go to these counties, which is my ultimate goal.

I’m not afraid of risking things, whereas many Japanese people are afraid. I think that risks are essential for growth. What I always have in is that, I’ll be in the front-line of risking things so people can be encouraged, and what I do give people inspiration to challenge themselves.

You have worked at a prestigious university in Japan, Tokyo University. You also did job-hunting and were offered positions from corporations. What made you decide to go abroad while you could have lived a so-called “elite” life in Japan and where did your courage come from?

At job interviews, I was told by corporations that I would mess up the harmony within corporation because I “surpass” other employees. I was open about my childhood and past experiences and I was told that they won’t be able to handle me, while saying they are sure I’ll make a great leader. Then I thought, I don’t suit working in groups or in corporations. So I decided to work on my own but I also realized that I need to speak English. Then I decided to become a stand-up comedian and went to Australia to study English at a language school.

I want to ask you about your childhood and touch on your experiences about neglect and abuse, if you’re comfortable with it.

Of course.

In the past consecutive 27 years in Japan, the number of reported child abuse has been increasing every year. There are more than 50 deaths of children in Japan annually, caused by abuse. Every week, at least one child passes away because of abuse or neglect. I assume that the increase is related to the change in definition of what constitutes child abuse and the awareness towards these issues are getting higher. As you have experienced traumatic experiences during your childhood, I’d like to ask, what can we do to raise awareness towards child maltreatment, and what are the things that we can do other than directly dealing with such issues when we come across them?

To people who have not experienced child abuse, it’s considered an imaginably huge trouble.

I was abused by my mother since I was very small. I had cuts, cigarette burns and bruises but I took all forms of violence as twisted forms of love. When people came from child services, all I had in mind was that I don’t want to be taken away from my mother away. She is the only mother in the world for me. The staffs came multiple times to our home when I was 5 or 6, asking if I was okay. They sometimes came in early mornings and asked me if I could let them in, and asked me about family environment. They also asked me to show my body. I told them multiple times that I was okay and told them to leave.

I understand that from outsiders’ perspective, they believe it’s the best to protect children who are at risks of abuse by removing them from abusive or neglectful environment and give them proper education. They think that’s the best solution.

I grew up at a hospital from age 1 to 3. From age 4 to 5, I grew up at an orphanage in Tokyo. I think it’s fair to say the environment was worse than at my abusive home as there were lots of bullying at the orphanage. Children were put in small rooms where there were around 10 children in each of them, and we were told to play, but none of us knew how to “play”, or to communicate with each other or how to behave. Most of kids who are from abusive homes never learnt how to do these things. I remember kids gathering in the corner of the rooms, asking for the lights to be turned off while crying. That’s the reality of orphanage. Many people report the police as they think it is the best to remove kids from toxic environment at home and afterwards they feel better about themselves, thinking they’ve rescued us. It’s a difficult issue.

There is a foster-parent system in Japan. There are foster parents who genuinely want to take care of orphans, but there are foster-parents that come to the orphanage to look for servants. Children who are at facilities are mostly not educated, nor have purposes to live. So, when they are asked by foster parents to do something, it gives them purposes and also joy. Getting a simple compliment makes them extremely happy.

For example, if the foster parents ask you to clean the house and you do so, you get compliments by them, and you feel that there is finally a purpose for them to exist. These foster parents turn kids into robots. There are many tests for foster parents to adopt children, but it’s not hard to fake being good parents.

Do you have friends who were adopted by foster parents?

I have 2 friends who were taken by foster parents. But most of my peers who are in the same age group, eventually got involved in crimes or were arrested and sent to reformatory school. They tell their stories as episodes of bravery. There are no boundaries between what’s acceptable and not, as most kids at an orphanage never get to learn what common sense is. They get spoilt by staffs who take care of them, because if they get told off for something bad they did, many kids have breakdowns, triggering traumatic experiences. Orphanages don’t want to be sued or being reported for issues like that, which can lead to the shutting down of the place. Teachers are all very kind and they don’t tell off anybody, but it is also unnatural.

I found it terrifying when I got away from my abusive mother and was taken to the orphanage, because all the staff were telling me that “it’s a safe place” with smiles on their faces. I found “overly comfortable” and “safe environments” to be very uncomfortable. The staff were overly kind to me, suggesting that I study or take part in activities while not trying to push me too hard which made me uncomfortable, and I felt spoilt. Many people end up thinking they can get away doing whatever we want.

One of my peers broke into a house next door and burnt a futon which led to the entire house burning down. Another peer was arrested, spraying a fire distinguisher in a restaurant. There was one who broke into a church and broke lots of bottles; it is hard to understand why he would do such a thing. These issues are common in orphanages as kids don’t have common sense.

I think that elementary schools’ role is to make children adapt to society and teach them how to get along with each other. Children in orphanages tend to fail to do so, and many refuse to go to school. I majored in psychology at university and studied about these children, and 90% of kids at orphanages go astray as they grow up.

Could you tell me about your experiences at elementary school?

Attending elementary school was hard for me, hardest out of all schools I attended. Other children despised me as I was an odd one and I wasn’t receiving the special care I had at the orphanage. It made me realize how the environment at the orphanage was not normal—everybody was overtly kind.

I think people in Japan try to keep as much distance with others and that’s the norm. From what I learnt from your experiences, it sounds like in both orphanage and elementary school, you were treated differently from others because you were labeled as a child who went through child maltreatment.

Kids who grow up in orphanage tend to behave oddly and rumors spread quickly in Japanese schools. Children are honest and also very cruel. If your father doesn’t attend a school event, a rumor that you don’t have a dad would spread immediately between children and their mothers.

Are there things in Japanese society that you wish would change in the future?

I used to think it was the best for all children who go through abuse or neglect to be taken care of at child-care homes. But there is a significant lack in numbers of these facilities and good ones are expensive and hard to afford.

Would you say Japan lacks funding for child-care homes?

Yes, and early childhood educators also don’t get paid well. It’s impossible to change the system on my own, but raising aware towards these issues is important and something that we can do. What I want to do is to give hope to children who had similar experiences as me. I want them to know that if they don’t try to change their own lives, nobody will, and that’s the cruelty of life. Children who grow up in child care homes or orphanages get special treatment and they fail to adapt to society, but I want them to know that even if they are discriminated by others, they are just like every other one and they deserve the best for them. I want them to go to school and be educated. When I was a student, I never missed a single day at school and I was a good student.

I was very lonely in elementary school and nobody talked to me, and I didn’t have any friends. I was having lunch one day and I stood up to get more food, but I somehow tripped. I was covered in food and milk. Usually, nobody talks to me in class as they labelled me as “gross” and many despised me. But at that moment, everybody was laughing as I tried to pull myself together, being embarrassed that I made a mess. I was so embarrassed that I almost threw up. But at that moment, I felt alive for the first time, and also needed by others. I made up my mind that this is what I will live for, and from that moment on, I tripped, failed tests and did silly things on purpose which made others laugh. That happened when I was 6 years old and I was lucky to find a purpose at a young age. If I didn’t, I would have gone astray just like every other child who were arrested for burning down a house and so on. There is nothing that distinguishes me and other people who are in reformatory school, and I’m just like every one of them.

In one of your interviews, you mentioned you seek environments that impose a burden on you. Do you think one day, you will find a comfortable environment where you don’t have to do that?

I’m too used to environments where there are lots of burdens and hardships. When I’m in an environment that is too easy on me, I feel uncomfortable. When I busk on the street, sometimes people kick the bucket, throw things at me or destroy my belongings. This one guy spilled whisky on my head and broke my DVDs. Whenever these kinds of incidents occur, it doesn’t surprise me as it is all expected. When these things don’t occur for a few days and everybody is kind to me, it makes me think that something seriously bad would occur soon, and they really do.

But I think most Japanese people try to live stable life while not risking things. Majority of Japanese people aim to get a stable job and have a family.

That’s true. Although that kind of a lifestyle also imposes pressure on you in different way, which might be the outcome of societal oppression in Japan. People try to not stand out which is also hard in a different way.

Definitely.

On a side note, is there a Japanese community that consists of young, new comers from Japan?

I’m not sure, I don’t have many Japanese friends in Toronto. There are some in Vancouver. There is also a big Japanese community in Sydney and I had around 70 friends there.

Was there a struggle you faced in Toronto as a Japanese, or as an Asian?

There are so many obstacles that I faced. I appeared out of nowhere in Toronto, this Asian guy in a yellow costume. I got asked by other buskers on the street if I have the license to perform on the street, and some told me to go back to my country as I am invading their territory.

Also, there are lots of Japanese people here who despise me. People tend to think of Japanese people as polite, but busking on the streets in Toronto made me realize how rude Japanese people can be. Some people come up to me and ask me if I’m Japanese, and when they find out that I am, they ask me “why are you doing such a thing?” which is rude.

I realized that Japanese people have a lot of questions. Most Torontonians are friendly to me and supportive of what I do but Japanese people tend to ask me questions like “Why do you use buckets instead of using real drums?” “Which part of Japan are you from?” and things like that. Japanese people approach me and these interrogations start. I hate it when they ask me these questions even though they have no interest in what I do.

Do you think they throw these questions at you because you are Japanese, and you’re doing something they don’t understand or approve of?

I think so. 99% of Japanese people who approach me are like that. I have another Japanese friend who also busks, and Japanese people approach my friend asking, “how much money do you make in a day?” which is not polite.

I sometimes think about why Japanese people have so many questions toward me, and it’s not that I don’t understand where they are coming from. But I think it’s because that their impression towards street performers are entirely different from what people think about them in Canada. When I was in Japan, I used to think of street performers as someone who are not good enough to perform at actual concerts and I think I used to look down on them. But in North America, I think it’s entirely different and people tip performers with respect. When I was in Japan, I never tipped street performers. But here in Canada, many people do, and they talk to them and take pictures with them. It’s entirely different and I think that is why what I do is beyond Japanese people’s understanding.

Maybe there’s a sense of discrimination towards this occupation.

Definitely.

Growing up in Japan, I felt that there are many Japanese people who are overly sensitive towards how other countries perceive Japan as. There are many TV shows where Japanese people ask for foreigners’ opinions on Japanese culture, and try to get approval from them.

There are two purposes of busking for me. The first one is to make Japanese people proud. They throw rude questions at me but when I talk to them, they learn that I’m a serious person and I have a purpose, and then they show respect to me as they understand where I’m coming from. As I mentioned before, I want to give courage to Japanese people, that someone like me is trying his best in Canada.

The other purpose of my performances is to challenge how westerners perceive Japanese culture is. On the internet, people see Japanese idols and robot cafés, which create an eccentric image, but for someone like me, who lived in Tokyo, I understand that there is a huge gap between how westerners perceive Japan is and how it really is. What I hear from my western friends, who visit Japan is that they were astonished by flashy lights of Tokyo first, but they find out that Japanese people are not as polite as they heard, and rooms are small and ceilings are low, and it’s not as great as they expected it to be.

I see people in Japan who don’t give seats to elderly people on public transportation. The majority of people don’t hold doors for others. People who stand close to the buttons on the lift don’t ask people which floor they want to get off, even if the lift is packed. People push others around to reach to the button without saying anything. They don’t apologize even if they step on others. I can’t speak on behalf of other cities in Japan, but Tokyo is like that and that’s where most travelers visit.

Japanese people are also embarrassed that they cannot speak English. For foreigners, there is an image of Japanese people being polite and also a certain image towards Japanese culture being eccentric with anime-culture and things. I want to maintain that polite yet eccentric image through my performances.

Would you say you’re trying to improve people’s image towards Japanese culture and the people there?

Yes, but there is also a huge contradiction to that. When I encounter Japanese people on the street while I’m performing, many say that they didn’t expect me to be Japanese and say, “its impressive that you’re doing these things while being Japanese”. When westerners approach me, they tell me that they could tell that I’m Japanese, saying “only Japanese people would do such crazy things” with a grin. I try to fill in this gap between these image towards Japanese people. I want to give hope to Japanese people while maintaining foreigner’s positive image towards Japanese culture.

Lastly, could we get a message from you to our readers?

My goal is to give hope to many people. If you’re facing struggles and life is hard on you, please think that there is a person out there on the street who is busking. I’m trying my best, so let’s try to do our best together. I don’t like telling people “ganbatte kudasai (loosely translates to do your best)”, as its too formal and also it can be pressurizing to people who are already trying their best. I know that the intention of these words is not bad, but still I try to avoid using that. So, instead of telling people to “do your best”, I want people to know that we are in this together. You are not alone.

http://www.tk-entertainer.com

Instagram

https://www.instagram.com/tkentertainer/

Twitter

https://twitter.com/tkentertainer

GoFundMe (I wrote about myself here)

https://www.gofundme.com/when-i-was-young-the-world-didn039t-need-me